Teaching writing can be a frustrating experience. Students will exclaim that they don't know what to write, so there's a failure to launch. Or, they create unfocused, rambling pieces that are hard to wade through. Often, superficial essays and narratives lack detail and sophisticated use of language. But...what if you could turn that around, so teaching students to write was rewarding? What if your students were actually engaged in the process? That can happen, especially if you try 5 ways to use learning stations for teaching writing.

Now, the strategies I'm about to share can be delivered in other ways, but stations are special in that they add an extra layer of focus and organization. By providing students with the time and space to zero in on certain skills and steps, it can prevent them from feeling overwhelmed.

Best of all they allow your students to get out of their seats and move, something they always appreciate.

1. Use learning stations to provide inspiration for your writers:

Let's begin here, since it can be so hard to get students started. I'm pretty sure that if you had a dollar for every time you heard "I don't know what to write," you'd be poolside somewhere, sipping something delicious instead of grading papers.

"I don't know what to write" can be due to a lack of attention or effort but, most often, the student is sincere and really doesn’t know how to start. They need to "see" how it's done. So, before you start a writing unit or assignment, spend some time priming the pump with some inspiration for your students.

Short mentor texts are perfect for this. Select ones that illustrate the techniques or formats that you want students to learn, and choose ones that are short enough for students to read relatively quickly. I like to aim for half a page or less - unless students will be working at only one station for most of the class (more on this below).

These inspiration stations also allow students to build the skills and confidence they need to create longer, more detailed pieces of writing.

There are many ways that you can create "inspiration stations," but these are my faves:

✅ Create multiple stations with mentor texts that illustrate the same technique or genre:

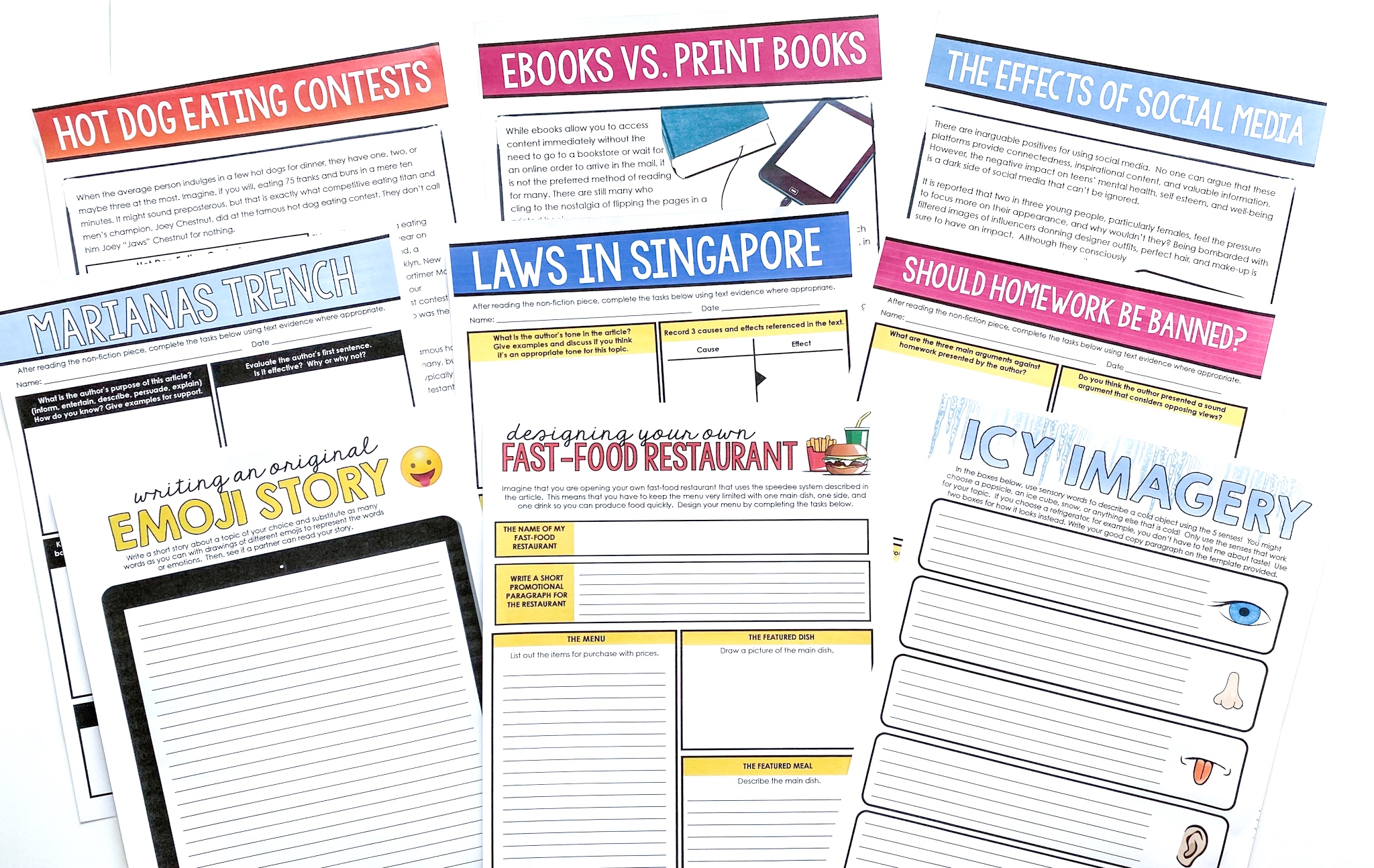

If you are introducing something specific, like narrative or persuasive writing, you can inspire your students by using a variety of short texts that illustrate a particular skill you want them to learn.

After getting a lesson on the technique, students move onto stations to get some practice with using it. For example, I have a series of mentor texts that illustrate how fiction writers use repetition and parallelism in their narratives. Each station has a different mentor text and students need to identify how the writer used these techniques. Then they use a starter sentence to create their own piece of writing modelled after the mentor text.

Or, if I want my students to practice using dialogue to create character, move the plot, use sensory imagery, etc., I will find mentor texts that will inspire them to use these strategies in their own writing. I put a different example at each station for students to read and imitate.

This can be done, of course, with any technique or genre of writing. Just decide on your focus, find the mentor texts, and set up your stations. The work students do at each station can be turned in for a grade, or they can just use it as inspiration for a longer piece of writing. Regardless, they are building their writing muscle through the process of visiting each station.

✅ Create stations that focus on different techniques, skills or genres:

In this case, the students will encounter something different at each station. If you are working on narratives, for example, station one might be about showing, not telling. Station two is focused on using dialogue, station three is about word choice, station four shows students how to use imagery and figurative language, and station five is about conflict.

Or, if you are doing a full workshop approach, you may have a narrative station, a persuasive station, a poetry station, etc. This approach provides students with a greater variety of mentor texts and ideas that can inspire them to try a new technique or genre.

When you create inspiration stations using mentor texts, you can allow 10-15 minutes at each station before students rotate to the next one. If you want to give them longer pieces to read and work on, you might send them to only one or two per class.

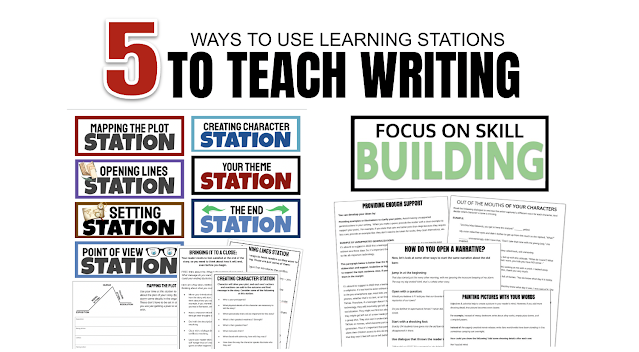

2. Learning stations can focus students on skill building

The other beautiful thing about using learning stations to teach writing is that they allow students the freedom to work on the skills they need to improve. With a traditional full-class approach, all students are working on the same thing. Tanner and Nicki, who have mastered transitions, have to sit through the lesson and activities on transitions when what they really need to work on is using more sophisticated language. Mia, also a confident user of transitions, would prefer to work on writing more engaging introductions.

With learning stations that focus on different skills, students can go to the one that best serves them. This will not only help them build their skills, but it makes them feel like what they are doing in class is useful to them. Rather than feeling frustrated or bored because they are sitting through lessons and activities they don't need, they will come away feeling like they accomplished something worthwhile. Thus, stations can help with engagement.

These stations are similar to the inspiration stations, but there is more of a focus on building the skill, so the tasks that you require may take more time. Once again, if you are working on narratives, you may have a stations focused on using dialogue. Along with mentor texts, you may provide handouts that illustrate some of the rule of using dialogue. Students may do practice exercises or use what they learn in their own writing.

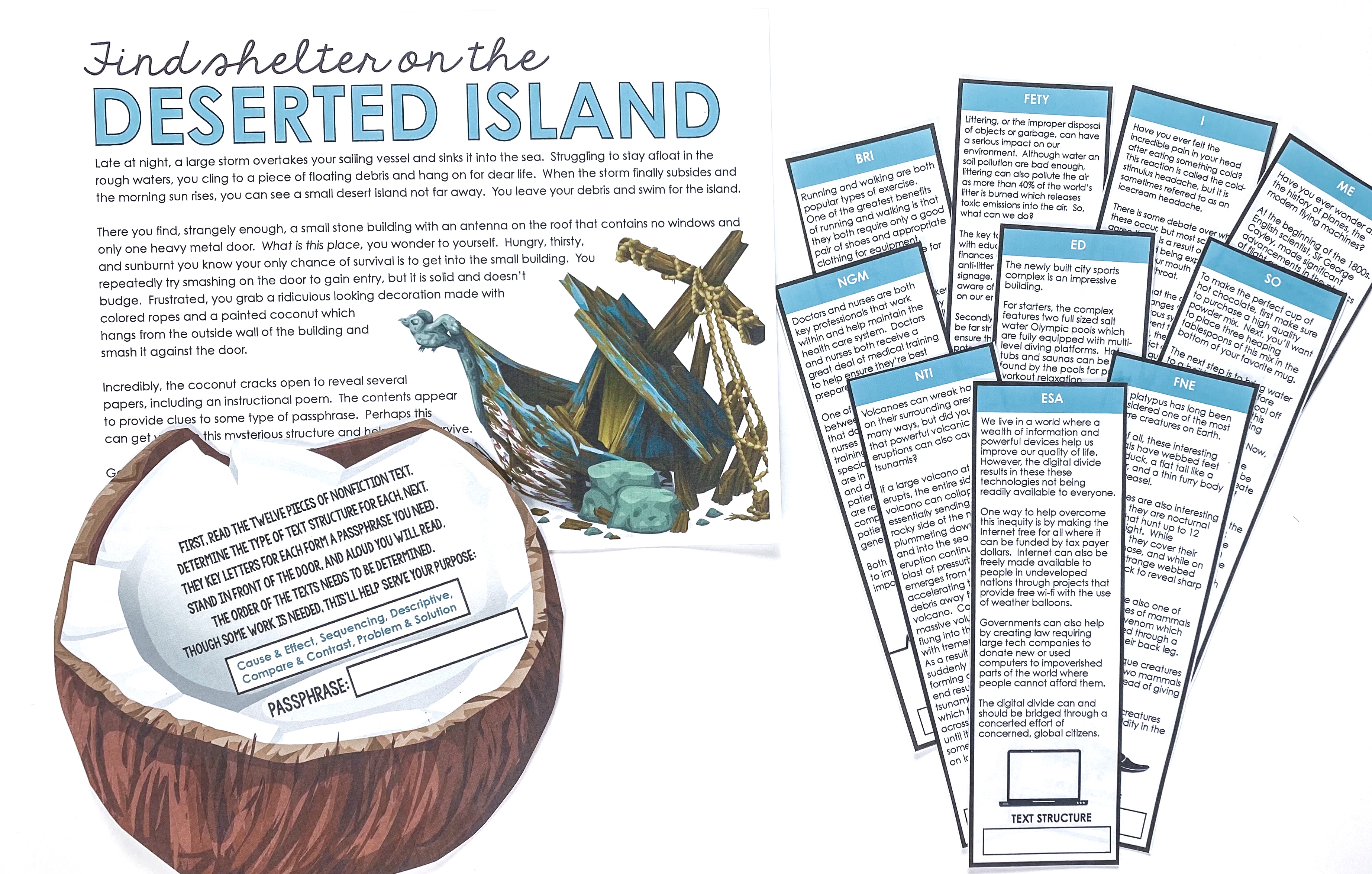

3. Use writing stations to focus on the steps of the writing and revision process

One of my favorite ways to use learning stations is to help students focus on the process. Prewriting stations are a wonderful way to get students to start to explore ideas, ones they can put together into a draft when they are done. For example, when my students were writing narratives, we would begin with brainstorming ideas for a story - just a rough sketch.

Then, the next day I would set up prewriting stations and they could play around with ideas for the setting, the characters, etc. It didn't matter what order they went to these stations, as it was an idea generation process only. And, the next day, when they began writing their drafts, students were ready to dive in as they had all kinds of ideas they wanted to try.

Another very effective way to use learning stations is to focus students on the process of revising their writing, something they can be reluctant to spend much time on. But once they have a first draft written, you can have them spend time at stations that guide them through the process of taking a careful second look at what is in the draft.

At these revision stations, students will be prompted to evaluate their introductions and conclusions, to play with their word choice, to check to see if they have enough detail to support their points and sentence variety to make their writing flow. You can create a station for any step of the writing process that you have been focusing on.

When students rotate through these learning stations, they spend far more time on the revision process than they do when you just tell them to revise. The stations allow them to focus on one thing at a time and so they are less overwhelmed and more likely to do the task well. The end result? Much better written final copies.

4. Teach writing skills with a teacher-led feedback station

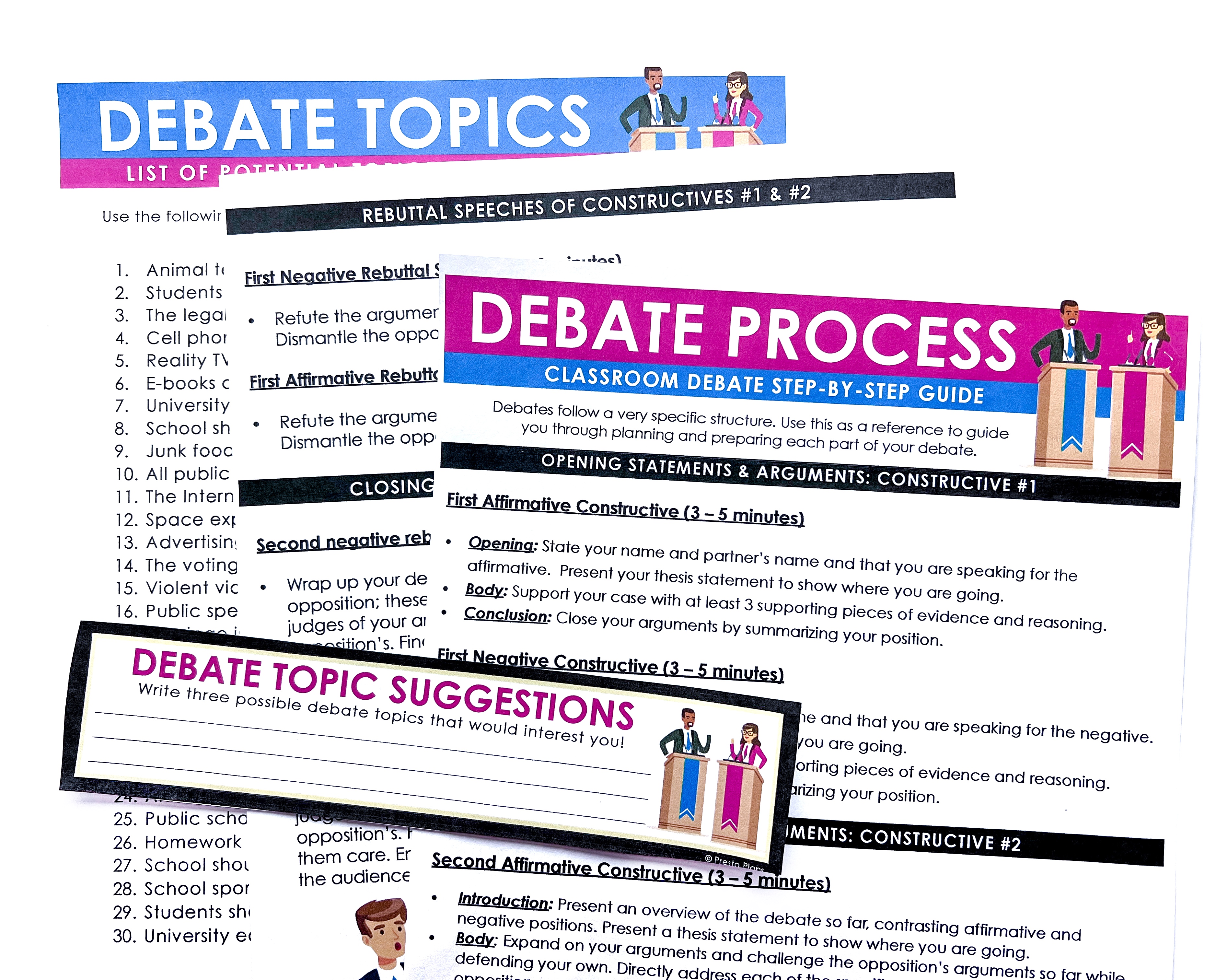

One of the fastest and most effective way to give students feedback on their writing is face-to-face and a stations format will help you do that in a focused and organized way.

When your students are busy and focused at the other stations, you can be working one-on-one with someone - or even with a small group.

The best way to do this is to give your students directions before they come to the station. They need to make sure that they are focused on one or two things only so you can quickly give them feedback in class. You could be giving everyone feedback on the same thing, or students could zero in on the areas that they are struggling with.

This can also happen at a peer feedback station.

5. Use learning stations to focus & organize a writing workshop

Writing workshop stations are the perfect way to keep students focused and on task during the workshop process. Unlike a more traditional format that has students working on the same assignment at the same pace, writing workshop gives them more freedom to pick and choose what they will work on.

Writing workshop stations are the perfect way to keep students focused and on task during the workshop process. Unlike a more traditional format that has students working on the same assignment at the same pace, writing workshop gives them more freedom to pick and choose what they will work on.

While this can be wonderful for our students, it’s a little harder for the teacher to organize. That’s where learning stations come in.

You will can set each one up to focus on different stages of the writing process with handouts and/or short mentor texts. Then, students can choose the station that works best for them.

When you use stations for writing workshop, students who need direction can find a focus, and you will have to spend less time dealing with "I don't know what to do next." This will mean you're freer to help students with specific questions or to conference with them about their writing.

Managing & Organizing Stations

So, those are my 5 Ways to use learning stations for teaching writing. If you like the idea of using stations to teach writing, but you just aren't clear on how to organize it all or manage your class when they aren't doing the same thing, click here to grab some ideas and strategies you can try.

Check out these ideas from my friends at the coffee shop:

Showing, not telling from Presto Plans

Symbolism stations for The Outsiders, The Daring English Teacher

Jackie, ROOM 213

.png)

.png)

.png)